Face to Face

The importance of reciprocal expressions between a baby and an adult carer, and finding opportunities that enable it, are explored by Anne O’Connor…

Read the article

Practitioners should acknowledge the feelings that separation can trigger in a young child, a parent and themselves, says Anne O’Connor…

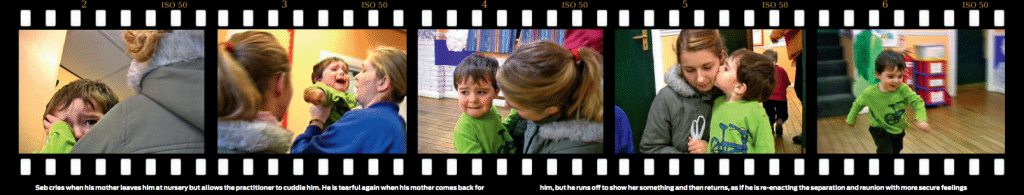

Seb and his mother arrive at nursery. Although he can handle being away from his mother for short periods, he is still finding the transition from home to the setting quite traumatic. He cries when mum has to leave him, but allows the practitioner to take him from her and give him a cuddle even as he reaches out for mum. Later, when mum arrives to pick him up, he is a bit tearful at first and clearly relieved that she is back. But he isn’t clingy and recovers quickly. He is keen to tell mum about his day and runs off to show her something. He then runs joyfully back to mum and snuggles up to her. Giving her a kiss, he tells mum he missed her.

1: In their book People Under Three, Elinor Goldschmied and Sonia Jackson wrote ‘we can never remind ourselves too often that a child, particularly a very young and almost totally dependent one, is the only person in the nursery who cannot understand why he is there’. (Goldschmied & Jackson 1994 :37)

Even though Seb has had enough reassuring experiences to know that his mother will be back later to collect him, he is still distressed and the transition process from one carer to another is traumatic for him. It is probably traumatic for his mother, too, as she hears his cries and sees his distress. Both of them benefit from the presence of a sensitive practitioner to soothe and understand their anxieties and concerns. What they don’t need is someone who tells them they don’t need to be sad or miserable or uses distraction to ‘fix’ the child’s distress. Having their feelings and fears acknowledged, honoured and accepted is an important part of the transition process for the child, and valuable for emotional health and well-being in the longer term.

For some children the pain of separation is like a physical pain. As Margot Sunderland comments in her book The Science of Parenting, if we take a child’s physical pain seriously, then we must also do the same for their emotional pain.

2 A child who cries when separated from their primary attachment figure is just doing what comes naturally, and for very good reasons. The human infant brain has a strong instinct for survival.

To a small child dependent on the proximity of a caregiver for their survival, separation poses the very serious threat of abandonment. The brain triggers a distress response and the child cries, because this is the most effective way an infant has of communicating. It is effective because the cry of a child, in most cases, triggers an automatic response in an adult brain. We are programmed to be unable to ignore it.This is a fundamental aspect of attachment theory that has been borne out by more recent developments in neuroscience, allowing us to understand exactly what is going on in our brains at times like this.

The separation distress system in a young child’s brain is hypersensitive and constantly on the alert for the threat of abandonment and anything that might threaten the child’s survival.

Unlike the babies of other mammals, human infants are not immediately mobile and self-reliant; they can’t run away from predators, or feed themselves. Their brains are also not fully developed at this stage, so their instinctive ‘lower’ brain is ‘in the driving seat’ (Sunderland 2006: 22). But over time, the frontal lobes (or rational ‘higher’ brain) will develop and allow the inhibition of the separation distress system so that it can become less sensitive.

As adults, we recognise and feel the strong emotions brought on by separation, but we have the rational understanding to know that our survival is not automatically threatened by it. ‘Mummy’s coming back soon’ will come to mean something eventually, but it is of no help to a young child who cannot yet process that in their brain.

This early instinctive fear of separation can last well into the first five years of a child’s life (Sunderland 2006). And just think how many separations (or transitions) children may be subjected to in our current systems for early childcare and education! The first major transitions from home and family, into care or education outside the home, all take place at a time when children’s brains are instinctively programmed to actively resist that separation.

3 Reunion can also be traumatic to a child. Seb seems distressed and tearful when his mother returns, although it is clear he has had a good time in nursery. It is so important that these daily transitions are handled sensitively.

Young children may be tired as well as relieved to see a parent, but a ‘bumpy’ transition can unsettle them and have a negative impact on the all important reunion.

Seb seeks physical connection with his mum first of all and shows her his distress at being apart from her. But he comes round quickly and is keen to show off what he has been doing.

Running off and returning joyfully for a hug and kiss with mum is a very physical response to the reunion, almost as though he is re-enacting the process of separation and reunion again, now that he feels secure that mum has returned. He is also able to tell mum just how much he has missed her, which is a good sign that he knows his feelings will be honoured and not dismissed as silly or pointless.

4 The key person approach has a powerful part to play in supporting these daily transitions. Sensitive and responsive ‘handover rituals’ support and reassure both child and parent as well as providing time and space for informal chats and sharing of information.

In the revised edition of Key Persons in the Early Years, Peter Elfer and Dorothy Selleck build on their earlier work with Elinor Goldschmied in describing a ‘triangle of trust’ between the child, their family and the key people in the school or setting.

This important three-way relationship is built gradually, over time and in a variety of ways, but ‘hellos and goodbyes’ are an important part of that relationship and can have an intensity all of their own.

As practitioners we have to check in with our own feelings when we respond to the distress of a child or parent struggling with separation. Their distress can trigger anxieties of our own, some of them much deeper than concerns about how we are going to handle an agitated, screaming child along with all our other responsibilities first thing in the morning.

As Goldschmied and Jackson commented, a child’s cries ‘may well have touched off a resonance in our own past experience which makes the situation doubly upsetting’ (1994:47).

Make sure that you acknowledge and accept your own feelings of distress when settling anxious children, by sharing your feelings with colleagues and supervisors. The availability of supervision and peer support is fundamental to the success and quality of the key person approach.

Getting in touch with our own feelings helps us to appreciate the feelings of the children and parents we work with, making us better able to support them through the challenge of daily transitions.

Article written by Anne O’Connor and published in Nursery World © www.nurseryworld.co.uk